My Perspective: Youth Climbing & Age-Appropriate Training

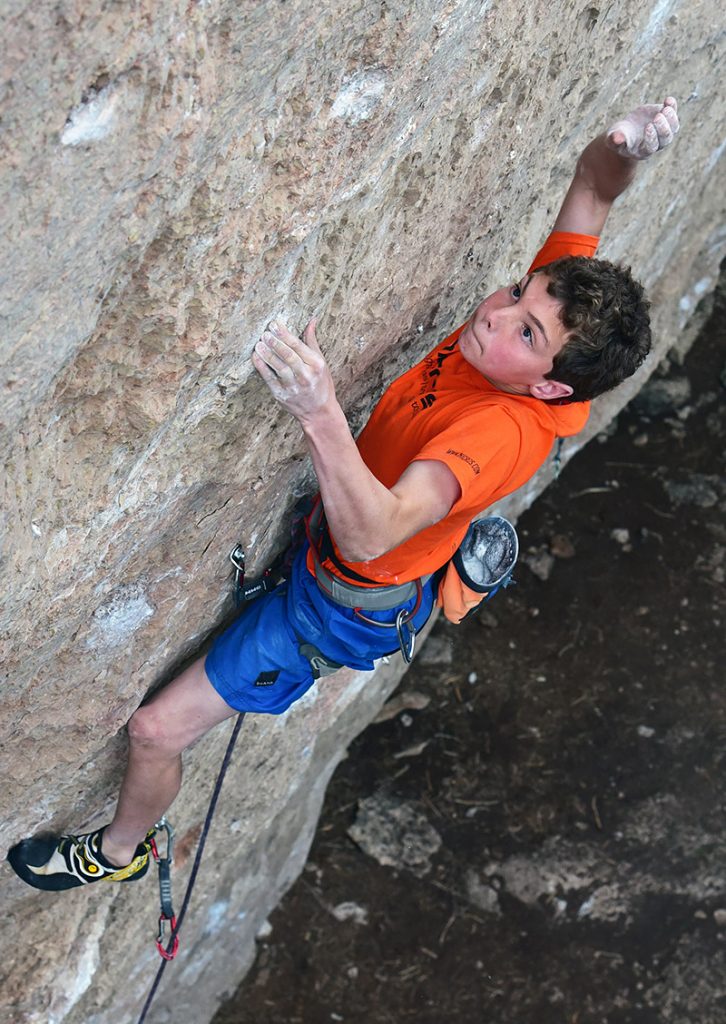

Jonathan Horst (14) on the first ascent of Sayonara (5.13c/d), Ten Sleep Canyon, WY.

The recent incredible achievements (V14, 5.14/8c ascents) of a handful of American and European youth climbers has made youth training a hotly debated topic. As veteran climber and both a parent and coach of two elite youth climbers, I’ve spent much time the last decade researching and developing a youth climbing philosophy that I feel it safe, effective, and appropriate. I’ve written extensively on this subject—and the importance of activity and developmental “balance”—and in this article I will share some insights and tips for discerning coaches and parents of youth climbers.

First and foremost, youths cannot simply be treated as “little adults,” who are given a proportionally less serving of an adult training program. Youth climbers have unique strengths and limitations, and they are vastly different from adults, both physiologically and psychologically. Until puberty is complete, the training focus should be on skill and mental development. Interestingly, preteen brains are predisposed to prolific learning of motor skills, and so they have a time-limited gift to develop and refine climbing skills at a much higher rate and with greater ease than adults.

As a primary skill training method, then, youth climbers should regularly be exposed to unfamiliar terrain and novel moves that demand problem solving and foster learning of new movement skills. An early focus on slab climbing (to develop footwork and balance) should expand to the more challenging terrain of overhanging walls and bouldering caves. When they’ve achieved a high level of proficiency at face climbing, youths should be exposed to cracks and corners, which demand acquisition of a vastly different set of skills. An early focus on sub-maximal bouldering and challenging toprope climbing should eventually progress to an introduction to lead climbing, although this is obviously a risky, headier form of climbing that is not to be rushed into prematurely. Some strong, talented youth climbers will develop the skill and confidence to begin lead climbing (well-bolted overhanging routes) by age eight or nine, while others may take years longer. There are no rules (no specific age) for when a climber is ready to lead—obviously this is a critical decision for the coach and parent to make together, and not something the youth climber should unilaterally decide.

Given a growing mastery of the fundamental technical and mental skills, some youth climbers between age eight and twelve are ready to be introduced to the challenges and joys of outdoor climbing. As with the introduction to lead climbing indoors, however, taking youths outside is a big step that should not be rushed. The earliest transitioners to outdoor climbing will be those youths whose parents are experienced climbers themselves—this way the parent can be responsible for making the tough calls on what climbs are safe or unsafe for a youth to attempt. For those kids without a climbing parent, it’s best to wait until at least thirteen to venture outdoors—and even then, to do so only in the presence of a mature, qualified instructor.

What about strength training? First, you can disregard the old wives’ tale that “strength training will stunt a youth’s growth.” While an extensive, high-intensity strength training program is inappropriate until late in puberty, a limited amount of age-appropriate strength training can be beneficial. Here are some basic guidelines by age.

Prior to the adolescent growth spurt, most apparent strength gains come from motor learning, not hypertrophy (muscle growth), and so any manner of extensive strength training is unnecessary and largely a waste of time at this age. Therefore, developing climbing-specific strength is simply a matter of following through with a consistent schedule of climbing. Use of a few supplemental climbing-like exercises is fine, as long as it doesn’t take away from movement training and climbing-for-fun time. Basic body weight exercises such as pull-ups, push-ups, core crunches and planks, and other similar gymnastic movements are the only strength-training exercises needed at this age.

It’s during pubescent growth spurt (ages 11 – 16) that some youths perceive a distributing decrease in strength-to-weight ratio as their weight gain outpaces their strength gains. Quality coaching is critical so that concerned youth climbers understand why they are apparently getting weaker despite a consistent climbing schedule. Some misguided youths will react by beginning a strict diet or extensive strength- or power-training program (or both) in an attempt to regain their physical capabilities—this unfortunate response often leads to injury, anorexia, or burnout.

Appropriate strength training will include a gradual introduction of some basic climbing-specific exercises such as pull-ups, lock-offs, a variety of core-strengthening exercises, and eventually some slow, controlled (static) campus “laddering” on large holds. Perhaps the most important addition to a youth’s training program is a small number of exercises to target the muscles that oppose the prime movers in climbing. Specifically, the training should target the extension-producing muscles of the chest, shoulders, and arms, and the small muscles of the rotator cuff. A modest investment—fifteen to twenty minutes, two or three days per week—will strengthen these important yet often overlooked muscles, and vastly lower the risk of the elbow and shoulder injuries common among avid and expert climbers alike. A final facet of effective training for youth climbers is flexibility training. While most climbing moves do not require extraordinary flexibility, quickly growing bones and muscles can lead decreased flexibility that will limit mobility and movement. A moderate amount of daily stretching can go a long way toward maintaining smooth, flexible movement.

As youth climbers approach their adult height (age 16 – 18 when growth plates fuse), they can gradually transition into a more intensive climbing-specific training program. Elite-level training techniques, such as one-armed pull-ups, campus training, and hypergravity (weight belt) training can be added incrementally during this multiyear ramp-up period. However, hold off on fully dynamic double-dyno campus training and advanced hypergravity-training protocols until after the eighteenth birthday (and even later in the case of a late bloomer). Strengthening the antagonist muscle groups remains an essential for muscle balance, proper posture, and reducing the risk of elbow and shoulder injuries—all potential issues for hard-training late-teen and twenty-something climbers.

What about injuries? Yes, there’s been a disturbing uptick in overuse injuries among youths, specifically fractures to epiphyseal (growth) plates of the fingers. Though most often observed in the hardest-training, hardest-climbing youths, all young climbers should be monitored for the onset of joint pain in the fingers. Growth plate injury often develops over time, first revealing as pain while crimping and, if not treated with rest, progressing to acute pain, swelling, reduced range of motion, and in the worst cases disfigurement that can become permanent. European research and anecdotal evidence here in the States reveal that double-dyno campus training and extensive high-level bouldering are the leading cause of growth plate injuries. Consult a doctor should injury concerns arise.

A final and most important coaching matter involves climbing frequency and degree of dedication to the sport. Understandably, many youths fall in love with climbing—to the point that they would like to make it their one and only recreational/sporting activity. It’s my opinion, however, that single-sport specialization should be discouraged before the age of 16. Research has identified a finite “golden period” of accelerated acquisition of motor abilities that lasts only through the early teenage years. This period of heightened neurodevelopment should be used to learn a wide range of sports skills that include running, jumping, flipping, throwing and/or shooting a ball, swinging a club or racquet, swimming in a pool, among many other wonderful and pleasurable ways to engage in skilled movement. A youth’s brief opportunity to learn at hyperspeed should be invested in learning more than just how to dance and pull up a rock wall. It’s my experience that young athletes can come to climb at a national-class level (or higher) while at the same participating in—and perhaps excelling at—one or two other sports and in school, as well!

About the author: Eric Hörst is an internationally renowned author, researcher, climbing coach, and accomplished climber of more than three decades. The rest of his climbing family includes wife, Lisa, and sons, Cameron (18) and Jonathan (16), both 8b+ climbers and footballers. Eric is the editor of the NICROS’ Training Center; his personal Web site is TrainingForClimbing.com.

Copyright © 2000–2019 Eric J. Hörst | All Rights Reserved.